Film Academy chief executive Bill Kramer dropped a reminder in Toronto on Saturday, that his group’s movie museum will in February devote space to the late director John Singleton’s Boyz N The Hood.

So here’s a gentle plea to the museum: Do this one without apology.

For the moment, the Academy and its museum are in apology mode. Next Saturday brings “An Evening With Sacheen Littlefeather,” complete with “a long-awaited statement of apology from the Academy” for what it describes as 50 years of boycott, attack, harassment and discrimination following Sacheen’s on-stage rejection of an Oscar meant for Marlon Brando.

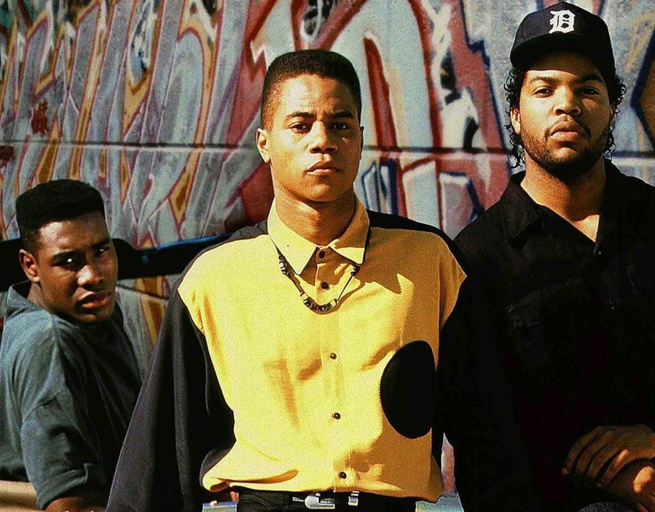

Columbia Pictures

The museum’s current “Regeneration” celebration of black cinema likewise comes with a note of regret. “We should have seen it long before now, but this is the day it begins,” Academy governor Ava DuVernay said of black achievement while introducing the show.

The apologies are perhaps in order. There will probably be more. But Singleton and his 1991 debut film deserve to be remembered for what they were: A proud and unapologetic presence in a studio culture that was happy to have them.

I knew John only a little, certainly much less well than did his executive-mentor and later collaborator Stephanie Allain, or the many young people who worked at his New Deal production company. While at Columbia, trying to produce movies in the 1990s, I had an office two doors down from Singleton’s. On one project, a never-produced action film, we were partners. Sometimes, we talked—enough that I could understand his quiet pride at having found his place in the studio system at the age of 22.

He was that young while making Boyz N The Hood. By the age of 27, he had made three studio features (adding Poetic Justice and Higher Learning), all for Columbia–a remarkable feat.

Certainly, Singleton had his frustrations, then and later. Allain could tell you more about those. Mostly, I remember a moment of personal uncertainty, as he wrestled with choices between potentially hot action projects or a deeper dive into black culture. He moved on to Rosewood, about a lynch mob, for Warner, and mostly stuck with black culture.

But the respect he commanded at Columbia was no less than that afforded the more seasoned filmmaker-producers—Penny Marshall, Harold Ramis, Danny DeVito, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Robert Duvall, John Woo, Adam Sandler, Wolfgang Petersen, Jim Brooks—who then populated the Sony lot.

Frank Price, the politically center-right studio chief who gave Boyz its greenlight, was certainly proud of the picture—so much so that he cast its young star Cuba Gooding Jr. in his own first production, the ill-fated boxing film Gladiator, upon leaving his executive post.

Jeff Stockwell, later a development executive for Maurice Sendak, and then a screenwriter, enjoyed underground celebrity status on the lot just for having spotted Boyz—or so the legend went—when he worked deep in the bowels of Columbia’s story department.

As for my action project, the studio took a flyer on it—after paying $5,000 for a brief exclusive reading period covering 52 pages from a then unproduced writer, a fairly bizarre deal—because Singleton was interested. They loved him that much.

Of course, the Academy loved Singleton enough to make him the first black nominee for its directing Oscar, in 1992. Singleton later told me his only wish was to lose the distinction of being the only black directing nominee. Others followed, Lee Daniels, Steve McQueen, Spike Lee, Barry Jenkins, Jordan Peele.

So there’s nothing to apologize for, nothing to regret, other than Singleton’s early death, of stroke, in 2019.